Music as a Bridge Between Greece and India

By Nektarios Mitritsakis

Indian classical music belongs to the same great family as Greek, Turkish, and Arabic music: the modal tradition.

In this music, every vibration and every melodic phrase is rooted in its relation to a fundamental note, which serves as the tonic of the scale. From this foundation, the subtle microtones between notes can be experienced and understood, revealing a deeper dimension of listening.

Two traditions that reach us from the depths of time are Byzantine music in Greece and Dhrupad in India. Both are centered on the human voice, monophonic yet rich in microtones, exploring sound through common scales and through a spiritual dimension, as their hymns and verses celebrate the Divine.

Both cultures also developed complex rhythmic patterns, measured in cycles of time: 7, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16 and more—sometimes in their classical expression, sometimes woven into daily life, as in the zeibekiko or kalamatianos.

The apparent simplicity of these traditions gives rise to an extraordinarily rich relationship between melody and rhythm. While they can be heard as entertainment, in truth, they are closer to a musical meditation, a profound form of healing through sound.

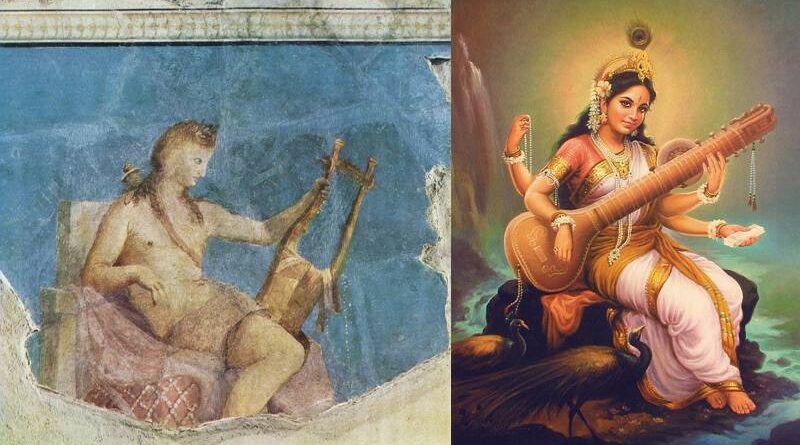

Common stories echo in both heritages: divine instruments given to humanity. Hermes created the lyre, later played by Apollo, while in India, Shiva is said to have fashioned the Rudra Veena—the most ancient stringed instrument, designed with the proportions of the human body.

Just as in Greece, we hear of Orpheus, who with his lyre could move even the walls of a city, in India, we encounter the Ragas: melodic frameworks that can influence the weather, and are assigned to specific hours of the day or seasons of the year.

From antiquity to the present, in both Greece and India, music and rhythm are inseparable from daily life, expressing the soul of each moment.

Whether as classical art, religious devotion, or folk tradition, the root is shared: a monophonic approach, rich in tones, modes, and rhythms.

Both traditions have much to gain by listening to one another—through the voice, the diversity of instruments, and the inexhaustible power of percussion.

The connection between Greece and India flows from the depths of history and continues naturally to this day. In ancient texts scattered across the world, we often find the idea that creation itself began with word and sound.

One old story tells that when God asked the soul to enter the human body, it refused, saying it would be a prison. Then God commanded the Angels to sing. The soul, carried away by the dance of sound, entered the body and remained within.

Since then, whenever the soul hears music, it remembers, even for a fleeting moment, its original freedom: another sense of time, a journey beyond the narrow boundaries of the body.

Read also:

MUSICAL TRAVELS WITH NEKTARIOS MITRITSAKIS by Haris Mitsuras, ΙΝDΙΚΑ 2005

DHRUPAD MELA by Nektarios Mitritsakis, ΙΝDΙΚΑ 2005 (in Greek)

RABINDRA NARAYAN GOSWAMI interview with Nektarios Mitritsakis, ΙΝDΙΚΑ 2005 (in Greek)